Aberdare Central Colliery accident and rescue

by Brian J Andrews, OAM - Coalfields Heritage Group (now the Coalfields Local History Association

The opening of the Aberdare Central Colliery in September, 1917, attracted numerous mine workers, many of whom erected and lived in shacks surrounding the new pit.

These mine workers soon brought out their families to join them at their shacks, thus the village of Kitchener, adjoining the colliery came into existence.

Kitchener was proclaimed as a village by the N.S.W. Lands Department on February 23, 1917.

Aberdare Central Tragedy

It is fitting that like Anzac Day, a day has now set aside to remember those who gave their lives in the coalmining industry, focusing on the Aberdare memorial.

However, the deeds of the rescuers mostly goes unrecognised.

Today, I bring you a story, not only of a tragic death, but also that of heroic deeds, and of a community brought together in such times. and when the sole survivor claimed that a small piece of chewing gum saved his life.

It was almost 68 years ago, when a large collection of miners gathered together, outside the gates of the Cessnock Cemetery, for an urgent union meeting, after farewelling yet another colleague killed in the Aberdare Central Colliery.

The funeral had been for William 'Gluey" Porter, who had been killed in the mine on July 11, 1938, a victim of yet another fall of coal.

This was the second fatality at the mine in just two weeks due to a the same cause. The victim of the first accident was James Harrower, who, earlier had been buried in the Aberdare Cemetery.

By a twist of fate William Porter had been one of the first to tender assistance a fortnight earlier, at the Aberdare Central mine, in the rescue the Harrower brothers, Peter and James.

The miners at that second cemetery meeting in two weeks, were fed up with the unnecessary loss of life in the industry, and so passed the following resolution -"We, the members of at Aberdare Central Miners Lodge, meeting at the graveside of a departed comrade, for the second time within a fortnight, to pay homage to another victim of the lack of safety of the mining industry, emphatically protest to the Parliamentarians, State, Federal, Legislative Council and Senate, and demand that no longer shall they waste their time in dealing with S.P.Bills, or any such other Bill, which is of no consequence to the community at large.

"We further demand that the politicians stop all parliamentary measures until this vital question - safety in mines - is dealt with by these respective bodies."

The resolution was put forward by Mr J.Duffin, and seconded by Mr M.Hickey.

Mr Duffin afterwards commented, "It would have been better if Mr Rowley James (from Pelaw Main) and Mr Eddie Ward, both M.H.Rs., had been expelled from the Federal House in a protest against the conditions under which the miners worked, instead of for the reasons that they were expelled."

At about that time it was reported that mine workers, and their families, were becoming extremely perturbed at the number of fatalities and accidents occurring on the northern coalfields, and it was generally felt that greater supervision was necessary.

Two Men Buried

A story of great endurance and perseverance, so typical in the history of Australian coalmining, was revealed at the Aberdare Central Colliery, on Tuesday, June 21, 1938, which brought a glow of pride to every man, woman and child connected with the coalmining industry.

One man had been killed, but another was miraculously rescued after a huge fall of coal occurred at the colliery at about one o'clock in the afternoon.

The rescued man lay buried beneath tons of coal for eight hours before he was finally extricated.

The fall, which occurred in the east dips of the mine, was estimated at over 500 tons. Some rescuers later described and estimated the fallen heap as being the size of several suburban houses, and reached as far up as 50 or 60 feet.

More than 150 miners took part in the rescue, all of the time facing the continual danger of further falls as they worked.

It was reported ...

Not only men, but boys who had never been near the coal face worked in a frantic endeavour to save the entombed men.

Unfortunately, several of them were injured, including the colliery manager, Mr Frederick Hemmingway (nicknamed 'Swinger'), who had both legs broken, as well as William Plumb, 27, of Cessnock, who lost the top of a forger when coping a coal skip, and also both Reginald Dixon and James Jenkins, who suffered abrasions when some timber they were setting near the fall, was dislodged onto them by coal falling from the top of the heap.

Many people gathered at the pit top during the afternoon and evening, and although it was bitterly cold, they remained until the body of the deceased brother, James Harrower, was brought to the surface.

A number of the rescuers had been working the day shift, but refused to leave the mine until the rescue work was completed.

Hundreds of other volunteers waited at the pit top for their call to go below.

The man killed was James Harrower, aged 42, a miner, married of Aberdare, and the rescued man, his elder brother Peter Harrower, aged 48, was also married.

Miraculous Escape

Peter Harrower showed great fortitude throughout his ordeal, even though buried beneath 50 tons of coal.

A remarkable feature of his miraculous escape was that he came through without serious injury. No bones were broken, but he suffered severe bruising to both legs, and an abrasion to the scalp, and naturally enough shock.

He chatted to his rescuers, and at times even directed them in their work.

His escape was nothing short of miraculous. He owed his life to the fact that the fall knocked skeleton timber onto a skip adjacent to where he was working, thus forming a protective cover over him.

He was caught by the fall, knocked sideways against the skip, with his legs being pinned by two large slabs of timber, which later delayed his rescue for some time.

Peter Harrower was brought from the mine at about 9.40 p.m., and the body of his brother extricated about 11 p.m.

The body of James Harrower was lying on its face when found. Its position suggested that he had received a warning of the fall and had started to run through the cut-through.

When comfortably placed in bed at the Cessnock Hospital, Peter Harrower was reminded of the old song, "Old Soldiers Never Die," to which he whimsically replied, "No, we're tough, ain't we?"

Peter Harrower was indeed an old soldier. He had been a miner at Minmi two decades earlier when he enlisted in the A.I.F., and fought in the Great War, serving in the famous 2nd Battalion, who fought at Gallipoli, France and Belgium.

Harrower, who had been buried once during the Battle of the Somme in France, remarked to one of his rescuers, "I wasn't nearly as afraid as when I was buried at the war. When I was buried then, all I thought about was my childhood, and many other things, but this time, I was confident you'd get me out. That's all I thought about."

From his hospital bed Peter also said, "I've been in some tight corners, but this one was the toughest. When I was hedged in, and could hear all of the falls of coal, I thought to myself, Peter, it's all up for you this time."

Alarm Raised

Leslie Brown, a road-layer, was the first to give the alarm. He was passing the bord where the Harrower brothers were working, and called a cheery greeting to them. Brown recalled, "Almost immediately there was a crash, and the whole place seemed to cave-in. There was as blast of air and I saw dust everywhere. I then realised that the two brothers were in terrible peril. I ran for about 100 yards, where I was able to call about six miners to assist in the rescue.

Les Brown said, "It was immediately seen that nothing short of a miracle could save the entombed brother. Word was immediately conveyed to the mine manager, Frederick Hemmingway, and in a short while, hundreds of men were on the scene ready to render assistance."

The first on the scene of the accident were Mick Cagney, "Bluey" Porter (who was killed two weeks later), Vince Forbes, and Harold Biggers, all of whom were working in adjacent bords

"We heard one of them moaning," said Mick Cagney. "We called out to Peter and asked how he was."

Peter replied, "How long will you be?" and a few moments later added, "I'm all right; I've still got my chewy!"

Cagney added that he had never seen a man in a worse position. He was almost completely buried, lying on his side. They could see one of his arms protruding but nothing more.

However, care was needed in his rescue, as there was imminent danger of more coal falling on him at any time.

Hundreds of Volunteers

When the accident was reported, the manager, Frederick Hemmingway, went below to supervise the rescue work. Volunteers joined him from almost every section of the mine.

Members of the rescue party had their first glimpse of Peter Harrower between 4 and 5 o'clock, over three hours after he had been buried by the coal.

They now had to work with far more infinite care, in order to prevent further tons of coal from falling from the roof onto him.

It was slow work. It would be another half an hour before they were able to get his head and shoulders clear, allowing him to at least sit up a little.

At this time an ambulance man offered him a drink through a tube, but he said he was alright, as he had been able to keep his mouth moist with chewing gum. He had been in the habit of always taking two packets of chewing gum into work with him every day.

"The chewing gum saved my life," he said, "had I not had it, then I certainly wouldn't have been able to hold out."

It took another hour and a half to move the coal away from the lower part of his body. The men at the fall had been forced to work in small relays.

As the rescue party got closer to Harrower, it was the job for men of small stature, small enough to burrow in like ferrets for short periods, raking the coal out with their bare hands.

Tom Gilmore had been endeavouring to make physical contact with Peter Harrower, but was too big to squuze through.

He was, however, able to reassure Peter that everything was being done to extricate him. Norman Wakeman then crawled through the opening, and was able to reach Peter, removing coal dust from his mouth, thus preventing him from suffocation.

The three Wakeman brothers, all of slight build, said to have had the energy and pluck of giants, performed prodigious feats in this dangerous work, earning for themselves the commendation of all present.

Even though they worked with the utmost care, every now and then small coal and slack would fall and cover Harrower. They frequently were forced to wipe clear his mouth and nostrils, which continually became covered in coal dust.

Had the coal weighing many tons above Harrower been dislodged, they too would have been buried along with him.

Whilst the grim drama was going on 1250 feet below the surface, and about a mile and a half from the pit bottom, the wives and family of the entombed men were anxiously waiting for bulletins in the colliery Ambulance room.

Everything was being done to comfort them, and a young lady was noticed conveying tea and refreshments to the anxious families.

Terrific Heat

The heat was so terrific at the accident site, that the men could only work in spells of ten minutes each. The fall had interfered with the air ventilation to that section.

Men were forced to discard their flannels and singlets, and in some cases worked only in shorts.

The smaller men had made it possible for timbers and rails to be placed above Harrower, making the position more secure against further falls.

When the men first got to Harrower they were amazed at his calmness and lack of panic. He said he had always been confident of being rescued, and didn't have the slightest fear about it.

Harrower told rescuers that he knew his brother was gone from the start. He said, "There was nothing on his side of the skip to protect him."

Dr Thomas Street and bearers of the Cessnock Ambulance, who went down the mine early in the afternoon attended Harrower when he was released.

It was a long way to the pit top. He was carried a mile and a half by S. Williams, J.Legge, H.Sanderson, A.Hitchcock, A.Bullen and T.Brennan, who worked in relays of about half a mile each. Jack Legge, one of those stretcher-bearers, now in his 90s, lives in a Cessnock retirement village.

The many hundreds of people who gathered at the pit top surged towards the shaft staging when it was announced that Harrower was being brought out.

As he was carried through the crowd. there were many cheers and calls to him. Covered in coal dust, with a cigarette in his mouth he happily answered his friends. From the pit-top he was taken to the colliery Ambulance Room, and then transported to the Cessnock Hospital by the Cessnock ambulance.

The crowd followed the stretcher-bearers to the ambulance and then the rush was on, to catch a glimpse of Harrower through either the vehicle's windows or doorways.

The first thing he asked for was a fresh piece of chewing gum, which was supplied by a young friend.

"Make sure my tobacco and matches are under the blankets," he instructed an ambulance man, indicating he still had a good presence of mind.

Click each photo to see the full-sized image.

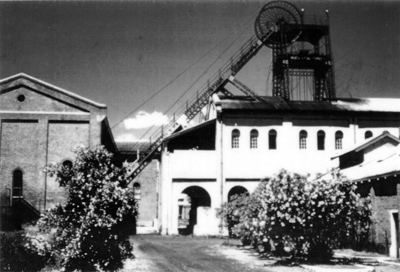

Aberdare Central Colliery [n.d.]

Headstone of James Harrower, Aberdare General Cemetery

Photograph by Ruth King, Australian Cemeteries Index

Restored poppet head, Aberdare Central Colliery, Kitchener

Jack Keily, 2010

Terrific Heat

The heat was so terrific at the accident site, that the men could only work in spells of ten minutes each. The fall had interfered with the air ventilation to that section.

Men were forced to discard their flannels and singlets, and in some cases worked only in shorts.

The smaller men had made it possible for timbers and rails to be placed above Harrower, making the position more secure against further falls.

When the men first got to Harrower they were amazed at his calmness and lack of panic. He said he had always been confident of being rescued, and didn't have the slightest fear about it.

Harrower told rescuers that he knew his brother was gone from the start. He said, "There was nothing on his side of the skip to protect him."

Dr Thomas Street and bearers of the Cessnock Ambulance, who went down the mine early in the afternoon attended Harrower when he was released.

It was a long way to the pit top. He was carried a mile and a half by S. Williams, J.Legge, H.Sanderson, A.Hitchcock, A.Bullen and T.Brennan, who worked in relays of about half a mile each. Jack Legge, one of those stretcher-bearers, now in his 90s, lives in a Cessnock retirement village.

The many hundreds of people who gathered at the pit top surged towards the shaft staging when it was announced that Harrower was being brought out.

As he was carried through the crowd. there were many cheers and calls to him. Covered in coal dust, with a cigarette in his mouth he happily answered his friends. From the pit-top he was taken to the colliery Ambulance Room, and then transported to the Cessnock Hospital by the Cessnock ambulance.

The crowd followed the stretcher-bearers to the ambulance and then the rush was on, to catch a glimpse of Harrower through either the vehicle's windows or doorways.

The first thing he asked for was a fresh piece of chewing gum, which was supplied by a young friend.

"Make sure my tobacco and matches are under the blankets," he instructed an ambulance man, indicating he still had a good presence of mind.

"MINERS ARE HEROES"

Waiting only long enough to down a cup of tea, and a few sandwiches, some of the rescuers, who had accompanied Harrower from the mine, returned to assist with the uncovering of his brother.

The crowd remained at the pit top throughout, until the body of James Harrower, which was found at 11 p.m., was finally brought to the surface.

One woman, who was crying as James Harrower's body was carried out. remarked to a nearby reporter, "Miners are heroes. Put that in your paper, They have been down there for hours risking their lives every minute. They don't care about themselves when they're getting a mate out."

As Mrs Peter Harrower was being congratulated on the providential rescue and survival of her husband, she simply said, "I'm a lucky woman. Those men who worked on the rescue were marvellous. They're wonderful men. I don't know how to express my thanks to them. I only regret that Jim's wife isn't in the same position as myself."

A number of accidents marred the rescue work. One of them being serious. The manager of the colliery, Frederick Hemmingway, had both his legs broken when struck by a second fall of coal.

Hemmingway was working in the tunnel dug to reach Peter Harrower, when a fall of coal, weighing about 25 hundredweight, struck him, breaking both bones in each leg beneath the knee.

"He never flinched a bit," said one of the rescue party. "The coal struck him and his legs snapped, just like matches."

"We were very lucky," said another. "Only a second before he had pushed a man named Bullen out of the way, fearing that he might be hurt working in that position."

An account of the second fall of coal, which caught manager Hemmingway, is told by Jack Delaney in his history of the collieries of the Greta Coal Seam.

All experienced coal miners listened, sometimes subconsciously, for noises of roof rock movement.

The noise warns them of any imminent danger, and from it, the miner gauges the time for a retreat.

During the progress of the rescue, a silence was called for, to listen more carefully for any roof noise.

The noise warning was such that the manager, Fred Hemmingway, ordered all to immediately leave the danger area.

He considered that a further fall was close at hand.

As Fred seated himself on the coal, someone asked, "What are you doing?"

He replied, "My God go quickly! I'm staying to hold Harrower's hand."

The hasty retreat by the rescue party was none too soon. As Fred sat on the heap, a further small fall of coal partly buried him, breaking both his legs.

When the rescuers returned, it took another two hours to free

Hemmingway, who was then carried out on an ambulance stretcher.

It was fortunate for Hemmingway that Dr Tommy Street was at hand, and with the assistance of ambulance men adjusted splints to his legs.

Many glowing tributes to the resourcefulness, and courage exhibited by Mr Hemmingway, both before and after his accident, which occurred at about 6 p.m., were made by miners who took part in the rescue work. His calmness, energy and leadership were described as marvelous.

Dr Tommy Street earned the gratitude of the whole of the Aberdare Central men. He waived the usual procedure of waiting at the pit top for the entombed men to be brought to the surface.

Going down below, he waited from 3 p.m. until Peter Harrower was rescued at 9 p.m. During those six hours he too helped in the work of the rescue. With him were two of the Cessnock Ambulance men.

It was recorded that ...

... feats of bravery and endurance were performed, which on the battlefield, would have earned high decorations. Each and everyone who took part in the rescue were heroes.

The Women Workers

The afternoon shift at the colliery did not start, but volunteers from that shift took part in the rescue.

Some of the men who had already done their day's work forgot their fatigue, and remained in the colliery until the body of James Harrower was recovered.

A willing band of women workers gathered at the colliery, when it became known that the rescue would take some time. They supplied sandwiches, cakes and tea for the rescuers, who left the mine at various times during the afternoon and night.

Kerosene tins of hot tea were even sent down the mine to the rescue party.

During the long weary hours of waiting, many of the Aberdare Central men said that June was their unlucky month.

It was in June the previous year (1937) when the railway crossing disaster caused the deaths of three of their colleagues, terribly injuring another three. Also in that year and month there had been another fatality at the colliery.

The real tragedy of the accident lies behind the fact that the mine nearly did not work on that tragic day.

At a union meeting, a matter had been argued for twenty minutes at the pit top in the morning, before it was decided to commence work.

The body of James Harrower was laid to rest in the Presbyterian portion of the Aberdare Cemetery, on Thursday, June 23, 1938.

Over a thousand miners marched in the cortege, which was headed by members of the Northern Executive and Lodge officials. Mr Jack Baddeley, M.L.A., also marched.

As the miners entered the cemetery gates they lined up on either side, as a guard of honour, in tribute to a fallen comrade.

The Rev. J.Faulkner, who officiated at the graveside, said he had only been three weeks on the coalfields, but already, in that short time, he had been greatly impressed by the heroism of the mining community. He would forever raise his hat to every miner he met.

He added, "This wonderful tribute to James Harrower affords ample evidence of the high esteem in which he was held by his fellow workmen and the citizens of Cessnock."

Before the year 1938 came to and end, the Aberdare Central Colliery would claim another three lives - those of William Porter, Allan Dyson, and James Ernest Hutchinson.

The cost of coal production, falling markets, increasing stock piles during the late 1950s and early 1960s brought about a series of changes in the coal mining industry.

Thus, it was due purely to economic reasons that the Coal and Allied Company ceased operations at the Aberdare Central Colliery on November 2, 1961.

Today, only one of the colliery's poppet heads remain, which, along with the colliery dam and surrounding land has, following a lot of hard work, been turned into one of the few tourist attractions featuring our coalmining heritage, a reminder of a bygone era.

Meanwhile the battle for safety in mines, which they protested and fought for in 1938, continues to this day. But still the accidents happen and lives are lost.

Brian J Andrews, OAM. Pioneering Days of the Coalfields - No.18, pp. 21-30

References

- Peter Harrower's war records

- "MINER KILLED AT ABERDARE CENTRAL COLLIERY." Singleton Argus (NSW : 1880 - 1954) 22 Jun 1938: 2. Web. 17 May 2013 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article81916589>.

- "GRIM DRAMA IN DEPTHS OF ABERDARE CENTRAL COLLIERY." The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder (NSW : 1913 - 1954) 24 Jun 1938: 3. Web. 17 May 2013 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article99463823>.

- "MINERS PROTEST MEETING AT CEMETERY GATES." The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder (NSW : 1913 - 1954) 24 Jun 1938: 7. Web. 17 May 2013 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article99463850>.

- "Aberdare Central Rescue." The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder (NSW : 1913 - 1954) 8 Nov 1938: 1. Web. 17 May 2013 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article99463372>.

More stories